Difference or disability?

June 2024

Hair cell ‘miracle’ brings backlash

By Paula DeJohn

The scientific quest to restore auditory hair cells reached another milestone in April, when an 18-month-old British girl named Opal, who was born deaf, was able to regenerate her cells in a clinical trial of a new form of gene therapy. She now hears “almost perfectly”, according to a report in The Guardian.

The trial’s success tops off a series of recent advances in research on the elusive structures, which transmit sounds to the brain. Perhaps the pace of progress is more than most people can adjust to, as reactions to the breakthrough in the trial, at Addenbrookes Hospital in Cambridge, have been decidedly mixed.

Many people quoted in The Guardian celebrated what some called the “miracle cure” and restoration of “normal hearing” but others stopped short at the words “cure” and “normal.” As columnist Oliver-James Campbell explains, “For some in the deaf community, words like these can be insulting.”

As HAH reported in the September 2023 issue, people have different ways of experiencing and identifying their hearing levels. But now, the discussion has expanded. As Campbell—who has hearing loss—says, “If the hearing world is listening, you’ll find that many deaf people would rather have support than miracle cures.”

Not the first time

For those who see themselves as part of the deaf community, and who use sign language, this isn’t the first time they have been wary of new technology. Readers recalled that when cochlear implants became available they presented a challenge: One could gain hearing, but then lose the community.

Notes one commentor, “It’s very likely there will hardly be any deaf people in the future, as cochlear implants are becoming the usual treatment for small children with hearing loss.” Adds another, “You can call something a ‘difference’ or say it creates a ‘culture’ but that doesn’t stop it from being a disability as well.”

The role of society

The level of social support for people with disabilities is also changing. Some observers think activists go too far when they demand accommodations while rejecting help with hearing improvement. Most are more nuanced. “Disability is relative,” says one. “Oppressed communities under siege from prejudice tend to coalesce as a defense mechanism…into fortified villages that tend to tribalism.” Adds another, “No thanks, I’ll take the miracle cure any time, and be able to interact with the vast majority of people in normal and unplanned situations…There isn’t going to be a BSL [British Sign Language] interpreter to follow me to the pub.”

Rebecca Taylor is a member of the Denver Chapter who lives in England, so we asked about her reaction to the news. She says, “Yes I did see this news and I thought it was amazing. How wonderful that they have been able to restore her hearing. It gives so much hope for families of children born with this particular type of faulty gene. I am always blown away by such advancements in medicine. I have often wondered myself what it would be like to have my hearing restored and if I would get my 'old self' back? I understand not all d/Deaf people would want this as it is part of their identity and culture, but having lost my hearing in my mid-thirties I have found it very challenging, so I would certainly jump at the chance.”

And, as an American, I thought it was depressing to read comments to the effect that “I got my hearing aids free from the NHS, but now I think they should teach BSL in the schools.” Free hearing aids? Meanwhile, there seems to be no stopping the march of technology that helps everyone: captions in theaters and on television, artificial intelligence, and all kinds of health research.

More on the miracle

Campbell, the Guardian columnist, takes care to point out that little Opal’s success in no way opens the floodgates of hearing restoration. Her condition, auditory neuropathy, the disruption of nerve impulses that connect the inner ear to the brain, is very rare. The most common form of hearing loss is sensorineural, where hair cells in the inner ear are damaged. Because the cells and related structures are responsible for transmitting sounds to the brain, hearing is diminished or lost. Unfortunately, mammals, including humans, are incapable of regrowing damaged hair cells.

But other creatures are not. Fish, birds and reptiles have the abilty to modify other inner ear cells to replace damaged hair cells. The secret is in their genes.

Among the latest studies is one by Harvard Medical School that attempted to reconstruct the genetic pathways that allow hair cells to divide and regrow. A research team led by Zheng-Yi Chen, an HMS associate professor of otolaryngology, reported creating “a drug-like cocktail of different molecules” that replicated the function of genes to regenerate hair cells in a mouse.

Counting their chickens

Another study, sponsored by the Hearing Health Foundation, concentrated on the restoration of hair cells in a chicken, and was able to map the genes and nerve connections in the inner ear. Researcher Stefan Heller, PhD, explains in Hearing Health News that the latest trick in creating hearing loss is to inject an ototoxic antibiotic, aminoglycoside sisomicin, into the chicken’s inner ear.

Unlike traditional methods such as loud sound exposure or systemic exposure to aminoglycosides, this approach induced profound inner ear damage at an unprecedented speed. It rapidly ablated all hair cells in the chicken’s inner ear, sparking our curiosity about the potential for these severely damaged chickens to fully recover from complete hair cell loss.

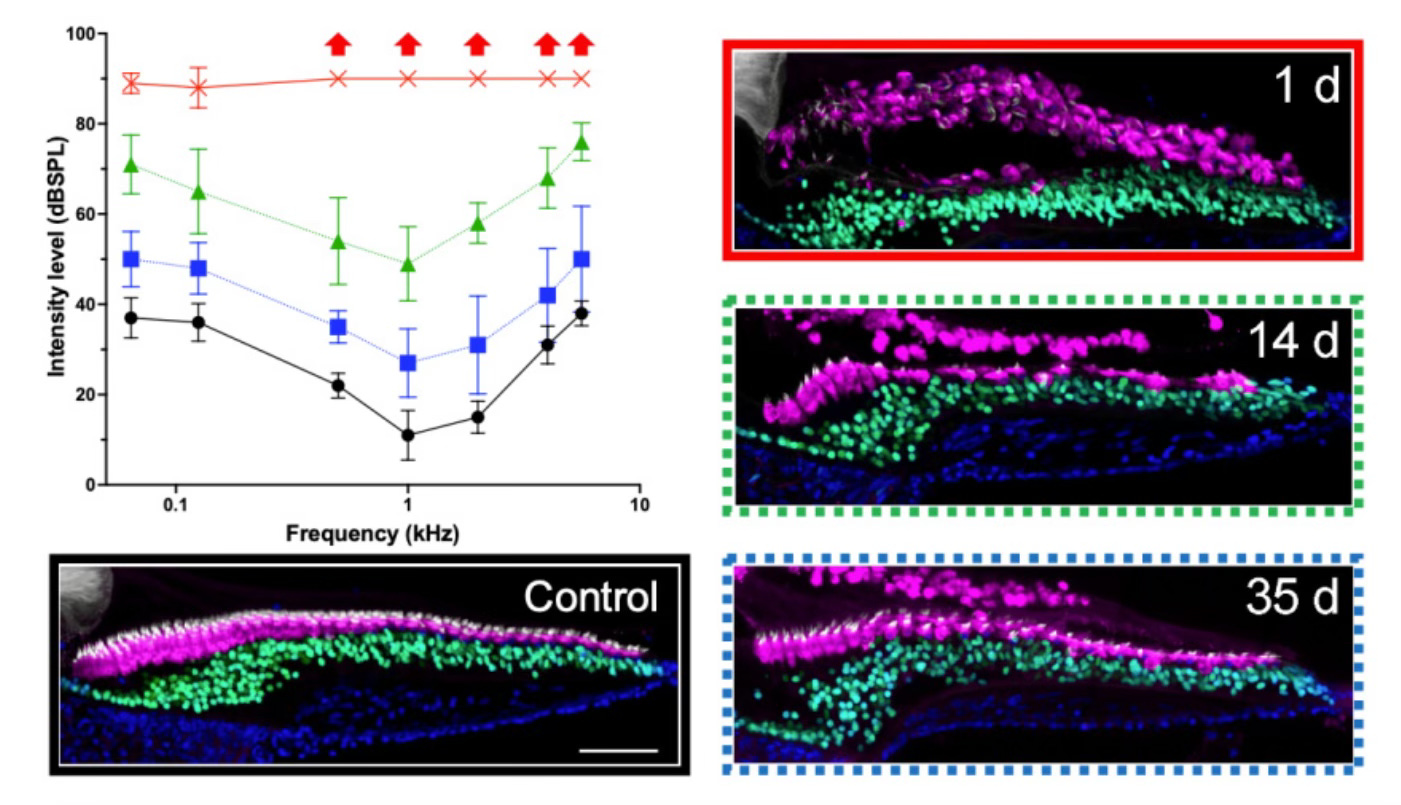

They were astounded by the result: new hair cells formed within five days, and by three weeks after the injection, the hair cells were fully regrown. By five weeks, or 35 days, hearing was fully restored. The graph below represents average results of six chickens, along with a control subject. The hair cells are shown in magenta, and the supporting cells, which did not die, appear green.

“I am astounded by the immense regenerative potential of the avian inner ear,” Dr Heller says. <>

Therapy can help with hearing loss

At the Denver Chapter’s May meeting, WellPower representatives Emily Osan and Shannon Alicea explained how the group supports people with hearing loss and their families.

WellPower, formerly the Mental Health Center of Denver, provides mental health services and homeless outreach, as well as addiction recovery help. Among the populations it serves are those with hearing loss.

While there is no direct connection between hearing loss and mental illness, some of the same therapies can help with both. WellPower offers group therapy and other types of counseling for the kinds of grief associated with hearing loss, and helps clients with the changes in relationships that can result from communication difficulties. “Communication provides the essential link between health and successful aging,” Emily explained.

Here’s how the WellPower web site describes those services:

Our approach acknowledges the importance of and need for direct communication and provides sensitivity to cultural affiliation and to the psychosocial impact of hearing loss. The counseling staff is fully fluent in American Sign Language (ASL) and Signed English. We have full-time staff interpretive services to insure comprehensive access to our continuum of care.

Hearing assistive technology systems (HATS) are devices that can help you function better in your day-to-day communication situations. HATS can be used with or without hearing aids or cochlear implants to make hearing easier—and thereby reduce stress and fatigue. Hearing aids + HATS = better listening and better communication.

WellPower has available the Comfort Contego® – a digital wireless assistive listening device (or HAT) for consumers with hearing loss to use during their appointments.

WellPower is a nonprofit organization serving the Denver area, with sites in other parts of the state. To make an appointment, call 303-504-7900 or (303) 504-6500 or visit wellpower.org. The organization accepts Medicare, Medicaid and private insurance payments.

Grants available

The Colorado Commission for the Deaf, Hard of Hearing, and DeafBlind is now accepting community grant applications for the fiscal year 2024-25 (July 1, 2024 -June 30, 2025). The application deadline is June 30. To apply, visit office.ccdhhdb@state.co.us or call 720-457-3679.

In past years, the Denver Chapter has received grants to fund captioners for meetings. The commission also has awarded a grant to Wynne Whyman for her Let’s Loop Colorado program.

Picnic plans

The Denver Chapter’s annual picnic has been scheduled for Saturday, July 20, but it won’t be at our usual place, Creekside Park in Glendale. Creekside is closing. Organizer Ann Monson is still working to arrange an alternate location. We’ll let you know more next month.

Free Botanic Gardens tour

Anyone age 50 or over can join AARP Colorado for a free morning at Denver Botanic Gardens on June 18. Free entrance will be from 9 am to noon.

Looking for comments

With this Substack format, readers can reply to every issue by clicking on the “Comment” button at the bottom of the screen. Some folks like to respond directly by email, which is fine, but by posting a comment, you can be sure all other readers will be able to see it, and offer their own views. Even people who are unable to attend monthly meetings will then have a chance to be part of the discussion. Try it, and I’ll be checking regularly to see how you think we’re doing. Paula DeJohn, editor

Creekside Park, the scene of many past picnics. Bike and hiking paths surround a volleyball court and shaded picnic area. Painting by Paula DeJohn

Very interesting article, and the advanced in medical science and hearing technology is amazing. It is just tragic that due to cost many solutions are out of reach for those who need it most!

Paula, What a beautiful painting! I didn't know you were a painter/artist! So nice!

Interesting info about research on restoring hearing. Sign me up!

Thanks,

Marilyn